Author’s Note: In 2014, I traveled to the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage near Cleveland, Ohio, to visit their exhibit, State of Deception: The Power of Nazi Propaganda. Below is the article, edited for updates, and video from that visit.

Featured image above: The Nazi Party had their own record label and customized records to target specific groups of voters. (Photo: Redwood Educational Technologies)

Article

‘Don’t judge a book by its cover’ is an idiom worth noting when studying propaganda. Propaganda had a central role in World War II and has importance in 21st century media and persuasion. For a compelling examination of the pernicious power of propaganda, visit State of Deception: The Power of Nazi Propaganda, a traveling exhibit curated by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The Nazi party rise to power in Germany

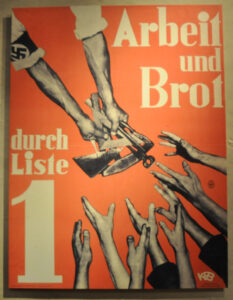

In 1930, the Nazi party was one of 30 political parties on the ballot in Germany. All of the political parties were promising to save Germany from difficult times after World War I. The parties all promised jobs and food.

But out of the cacophony of political voices, the Nazi party grabbed the attention of the electorate. By 1932, the Nazi party, with Adolf Hitler its leader, came to power. The Nazi party received 38 percent of the vote in the 1932 election, the most votes of any political party.

In 1933, German President Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934) appointed Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of Germany. Hitler then set Germany on a path to World War II and the Holocaust. During the Holocaust, six million Jewish citizens, including 1.5 million children, were murdered, a path never imagined by Hitler’s early supporters.

How did the Nazis ascend to power through a democratic process with many rivals?

Adolf Hitler had been an art student. He understood better than other politicians in his time how to use all media tools to deliver propaganda to the general public to win votes, according to Mark Davidson, manager of School and Family Programs at the Maltz Museum.

Mark defines propaganda as “a message containing truths, half-truths, or even outright lies that is crafted in a way to influence public attitudes and behaviors.”

Artifacts of propaganda

Mark explained that Hitler embraced all forms of media to deliver his message. And early in his rise to power, Hitler had a popular message. In 1932, he proclaimed the Nazi Party would put Germans back to work, put food on their tables and would extricate Germany from the harsh remedies of the Treaty of Versailles, the treaty that ended World War I in 1918. Germany was named as the sole cause of World War I in the treaty and punished severely for it. Hitler promised Germans he would correct what the Nazis believed was an injustice.

On display at the exhibition is a vintage phonograph. The Nazi party had its own record label producing vinyl records containing both popular music and propaganda. “It built the hipness factor,” Mark said. And the Nazis cleverly practiced what is now known as ‘niche marketing’ by targeting different groups of people with different records.

The formal name of the Nazi party was the National Socialist German Workers’ Party. Hitler understood the importance of a logo. He wanted a symbol that could be used on flags, posters, fliers, clothing and a myriad of other artifacts to immediately identify the Nazi party.

He borrowed the Nazi swastika from prior art. Stark colors of red, black and white were chosen so the Nazi logo could be seen from afar. The swastika symbol to this day evokes a flood of raw emotion and tragic memories of World War II and the Holocaust.

More than 400,000 American soldiers were killed during World War II liberating Europe from Nazi domination and defeating Japan after its attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

“Propaganda is a truly a terrible weapon in the hands of an expert,” wrote Adolf Hitler in 1924, according to a Maltz Museum press release.

By the 1930s, Hitler and the Nazis became propaganda experts eventually using media as a weapon of war.

“Hitler was an avid student of propaganda and borrowed techniques from the Allies in World War I, his Socialist and Communist rivals, the Italian Fascist party, as well as modern advertising,” Steven Luckert, U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum exhibition curator, said in a press release. “Drawing on these models, he successfully marketed the Nazi party, its ideology and himself to the German people.”

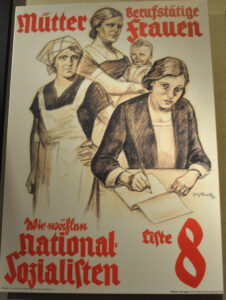

Nazi posters

Walking through the exhibition, the many Nazi posters are remarkable for the high quality of graphics even in the early days when the Nazi Party was coming to power. Mark likes to have groups study certain posters on their own to discern their intended target and message.

One poster depicts women of all ages in different roles. After trying to decipher the poster’s propaganda, Mark explained the message for the masses was that the Nazi party was not only for men but also for women. While it was true women could join the Nazi party, there was not one woman in a position of leadership, Mark explained. Through graphics, women are favorably depicted in the political poster (see below) in order to earn their vote at the ballot box. It was the poster’s sole purpose. The poster is an example of propaganda that was partially true but with an overall message that was false.

The exhibition includes videos, historical photographs, film strip reels, and other artifacts from the time. In addition, the museum is showing ‘Cartoons Go To War,’ a series of American cartoons created during the war by the U.S. Navy and Disney. The cartoons promoted the sale of U.S. war bonds to finance the war.

Mark hopes students will learn from the exhibition in order to apply those lessons to their lives as they are bombarded daily with media messages on multiple digital devices. Understanding the foundation upon which the message was crafted is crucial. Asking questions, studying written documents, and discussing the message with experts and peers will help form opinions and define actions in response to the message.

“Diagram an image like a sentence,” Mark advised.

For more information, visit State of Deception: The Power of Nazi Propaganda at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.